What is a peer-to-peer network?

- mysteriumnetwork

- Jun 25, 2020

- 9 min read

Updated: Dec 4, 2025

What is P2P (Peer-to-peer) technology?

For centuries, human connection has never been a simple equation. 1+1 often equals 3, sometimes more.

We had messengers who carried sealed letters, phone operators who connected our calls, and now Internet Service Providers who hook us into a matrix of other businesses, platforms and infrastructure owners just to send a simple email.

Perhaps the most perplexing and inconvenient way of communicating – the singing telegram…

Yet with the dawn of peer-to-peer (P2P) technology, the role of these middlemen (and women) has perhaps become obsolete.

P2P networks (and P2P software) allows 2 devices (and therefore, two people) to communicate directly, without necessitating a third party to ensure it happens. The technology has often been rejected and buried in the darker corners of the web, especially as corporations have taken over our communication channels. These businesses have dictated how we connect and communicate with one another for decades.

But before the web was ruled by the corporate letheans of today, it was once powered by the people who used it. This P2P ecosystem meant that users could connect and communicate with each other directly. The bluetooth in your phone functions similarly to this – you airdrop files directly between devices, with no need for any intermediary to facilitate or even see what files you’re sharing.

Maybe you remember Napster. They popularised P2P music file sharing. While you were downloading and sharing files from this platform, you were also spreading a new phenomenon which the internet made possible – community-powered, governed and owned technology that stretched into our social and economic realms.

Vintage P2P network. A window you recognise, even if you never used it. Source.

But first - what is the client-server model?

The internet that we know today is mostly made up of the client-server model. All machines or devices connected directly to the internet are called servers. Your computer, phone or IoT device is a client that wants to be connected to the web, and a server stores those websites and web content you want to access. Every device, whether client or server, has its own unique “address” (commonly known as your IP address), used to identify the path/route for sending and receiving the files you want to access

How does the internet “work”? A look at the client-server network model.

Servers store and control all this web information centrally. The biggest and most widely used ones are owned by companies like Google, Facebook and Amazon. These possess the computing power, memory and storage requirements that can be scaled to global proportions. It also means that a single server can also dictate the consumption and supply of resources and websites to users (clients), like you and me.

What is a peer in networking? How does P2P work?

Peer-to-peer infrastructure transforms the traditional role of a server. In a P2P system, a web user is both a server and a client, and is instead called a node. (Your computer or device technically acts as the node.)

Related: The ultimate guide to running and earning with a Mysterium node by sharing your bandwidth. Nodes power the network by sharing their resources such as bandwidth, disc storage and/or processing power. These can be shared directly and information is distributed evenly among all nodes within the network. These sorts of decentralised systems use shared resources more efficiently than a traditional network as they evenly distribute workloads between all nodes. Together, these computers equally and unanimously power web applications. Because there is no need for a central host or server, these networks are also less vulnerable from a security and network health standpoint, as there is no single point of failure.

What is an example of a peer to peer network? what is P2P used for?

“Peer-to-Peer mechanisms can be used to access any kind of distributed resources” There are many uses for peer-to-peer networks today. P2P software have characteristics and advantages that are missing from the web today – trustless and permissionless, censorship-resistant, and often with built-in anonymity and privacy.

P2P file sharing – BitTorrent – sync-and-share P2P software which allows users to download “pieces” of files from multiple peers at once to form the entire file. IPFS has also emerged, where users can download as well as host content. There is no central server and each user has a small portion of a data package. IPFS is the evolution in P2P file sharing and functions like BitTorrent and other torrent protocols. IPFS mimics many characteristics of a Blockchain, connecting blocks which use hash-function security. However, IPFS does support file versioning, while blockchain is immutable (permanent).

P2P knowledge – Decentralised Wiki (Dat protocol) – an article is hosted by a range of readers, instead of one centralised server, making censorship much more difficult.

P2P money – Bitcoin – where value is digitised, encrypted and transparent – and as easily transferred as an email. Computers or machines (nodes) with enough GPU power maintain and secure the network. Peers can store and maintain the updated record of its current state.

P2P computing power – Golem – decentralised supercomputer that anyone can access and use. A network of computers combine the collective processing and computing power of all peers’ machines. The connection grows stronger as more computers join and share resources.

P2P communication – Signal –perhaps the most popular communication app with end-to-end encryption and architecture mimics P2P tech. Their server architecture was previously federated, and while they rely on centralised options for encrypted messaging and to share files, this facilities the discovery of contacts who are also Signal users and the automatic exchange of users’ public keys. Voice and video calls are P2P however.

Peer-to-peer in many ways is human-to-human. These virtual and collaborative communities hold us accountable to each other and the technology we’re using. They offer us a sense of responsibility and comradeship. They have been called “egalitarian” networks, as each peer is considered equal, with the same rights and duties as every other peer. If we’re all helping to keep something sustained – a living digital community where responsibility is equally shared yet belongs to no one – then perhaps we can emulate these same lines of thought beyond our technical networks and into our political and social worlds.

Can a P2P network teach us about purer forms of digital democracy?

Popular peer to peer networks and platforms

The theory of P2P networking first emerged in 1969 with a publication titled Request for Comments by the Internet Engineering Task Force. A decade later, a dial-up P2P network was launched in 1980 with the introduction of Usenet, a worldwide discussion system. Usenet was the first to operate without a central server or administrator.

But it wasn’t until 1999, some 20 years later, that a P2P network really proved its potential as a useful, social application. American college student Shawn Fanning launched Napster, the global music-sharing platform which popularised P2P software. Users would search for songs or artists via an index server, which catalogued songs located on every computer’s hard drive connected to the network. Users could download a personal copy while also sharing music files.

Napster Super Bowl XXXIX Ad “Do The Math”

Napsters experiential marketing tactics during the 2004 super bowl, when they abandoned their P2P network to paid model.

Napster was the dawn of P2P networks “as we know them today”, introducing them to the mainstream. It has been suggested that peer-to-peer marketplaces – some of the most disruptive startups to grace the web – were inspired by the fundamental values and characteristics of Napster. Businesses such as AirBnB and Uber kickstarted the new sharing economy, but sold us the illusion of community. As conglomerates who are simply the middleman between our peer-to-peer transactions, we also become their hired workforces without realising it. This business model relies on us to supply our own homes, cars and time to create the sharing economy, while they simply facilitate the transactions (and take a cut).

With P2P systems, we can remove them from the picture altogether. If we decentralise the sharing economy, you become the user, the host and the network itself. As peers, we are incentivised to contribute time, files, resources or services and are rewarded accordingly, with no one taking a cut. Decentralised P2P networks are transparent, secure and truly community-run systems.

A strange sharing economy infographic by Morgan Stanely, who thinks everything can be shared – including pets?

Jordan Ritter (Napster’s founding architect), was quoted in a Fortune article:

“As technologists, as hackers, we were sharing content, sharing data all the time. If we wanted music… It was still kind of a pain in the ass to get that stuff. So Fanning had a youthful idea: Man, this sucks. I’m bored, and I want to make something that makes this easier.”

Napster soon became the target of a lawsuit for distributing copyrighted music at a large scale, and was consequently shut down just 2 years later. Yet this “clever-if-crude piece of software” demonstrated new possibilities for applications, and “transformed the Internet into a maelstrom, definitively proving the web’s power to create and obliterate value…”

Corporate profit, infrastructural control

While digital networking has led to an unprecedented evolution of our social and professional lives, the potential of peer networks to power those daily interactions took much of a backseat as the web started to take off in the early 2000’s. While protocols of the early Web 1.0 were founded upon decentralised and peer-to-peer mechanisms, centralised alternatives eventually took over.

Yet since centralised systems began to plant their roots deep into our internet infrastructure, the web has been slowly rotting away underneath shiny user interfaces and slick graphics. They make the internet less safe, with servers that are routinely hacked. It makes the internet far less private, enabling mass-surveillance conducted by cybercriminals and organisations alike. It makes the internet segregated and broken, rather than unified and democratic, with nations building impenetrable firewalls and cutting off the outside world altogether.

It’s said that P2P money poses a large threat to governments, who seem concerned that without regulation and oversight, these “anarchist” networks could grow beyond their control. The crackdown on cryptocurrency in countries with rampant human rights violations, corrupt governments and crippling economies only lends to the theory that peer to peer systems undermines the very foundations of traditional government structures.

Places where cryptocurrency seems to thrive, are often the same where censorship, corruption and economic instability.

First P2P Money. Next, P2P Internet.

Yet the common, centralised standards which were born out of corporate and political needs are failing us today.

It’s time to turn the tides if we want to surf the web on our own terms.

Peer-to-peer networks have opened up entirely new philosophies around social and economic interactions. Researchers from a 2005 book exploring the potential of Peer-to-Peer Systems and Applications believed that these networks “promise….a fundamental shift of paradigms.” The applications which formed in the early 1980s “can no longer fully meet the evolving requirements of the Internet. In particular, their centralised nature is prone to resource bottlenecks. Consequently, they can be easily attacked and are difficult and expensive to modify due to their strategic placement within the network infrastructure.”

In the past decade, we have seen a re-emergence of P2P protocols. These new community-powered networks are creating entirely new systems and services, that are evolving beyond the traditional concepts of P2P. This was kickstarted in many respects by Bitcoin. Its underlying blockchain technology redefined our understanding of P2P, merging it with game theory, securing it with cryptography and expanding its network with a common CPU (in the first few years, at least).

P2P access

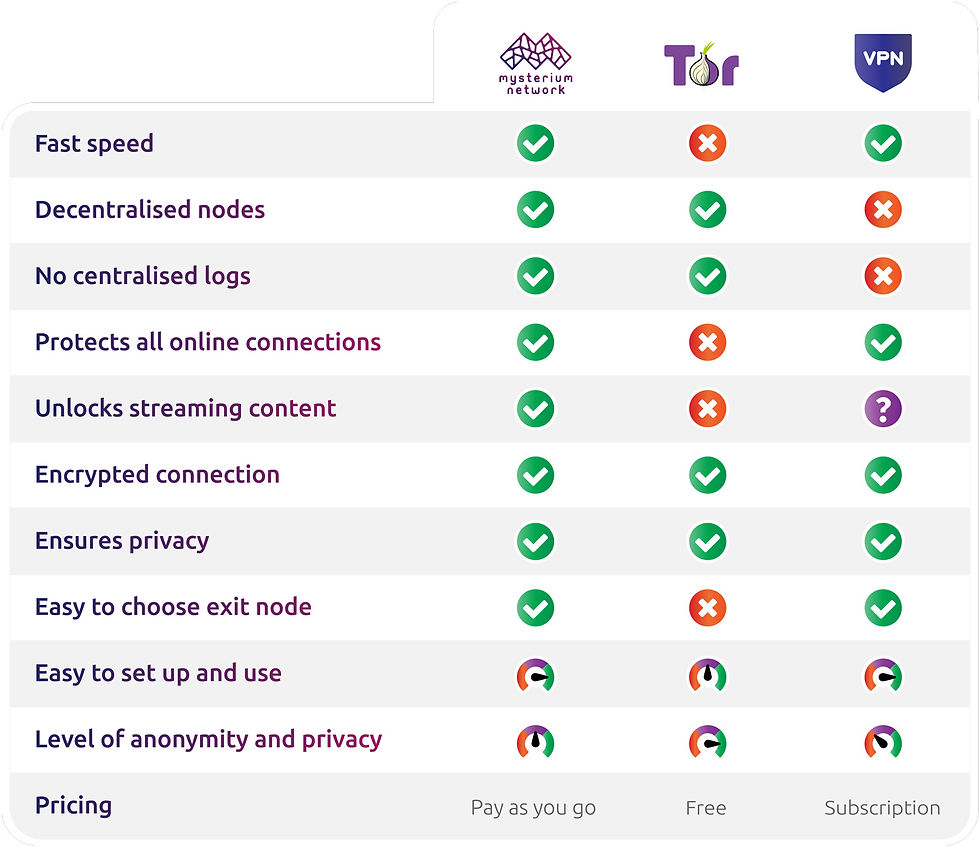

There are many P2P “layers” that can restructure the internet itself. A decentralised VPN is one such layer, offering P2P access to information.

This dVPN utilises a blockchain (the technology underlying Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies). Anyone can be a part of the network; your computer becomes a node, acting as a miniature server. This means it can help power the entire network by directly sharing its bandwidth or IP address – and be paid for it. There is no need for a host or intermediary. The bigger this distributed network grows, the stronger and faster it becomes. Its democratic and self-governing architecture creates an open marketplace that serves a global community in need.

A community-run VPN is different to a regular VPN in a few different ways. VPNs are businesses which exist to turn profit. Common VPNs own or rent servers that are centrally owned, and which could store logs of all your traffic without anyone knowing (in theory). You simply have to trust that they won’t do anything with this info. And while your data is encrypted, there have been cases of past hackings.

A P2P VPN instead leverages a decentralised network so that your encrypted data passes through a distributed node network, similar to Tor. A single node will never be able to identify you or your online activities, nor can authorities and third parties. In its decentralised form, a VPN pays people (nodes) for providing the privacy service. And as with most P2P systems, a decentralised VPN has no single point of failure or attack, making it safer and stronger than centralised alternatives.

Power of the P

Often perceived as a more rudimentary technology, the potential of peer-to-peer technology has been shoved to the digital back shelf for some time. But as the internet evolves as a social and economic landscape, it’s slowly starting to take its rightful place in the online realm. In its simplicity lies its beauty. The most complex and honest human interactions are always the most direct and transparent.

A P2P VPN is just one example of these many different applications. You can try the Mysterium VPN for yourself and experience how P2P works. There are versions for Android, Mac and Windows, currently free before our full launch.